The impact on Artistic Research

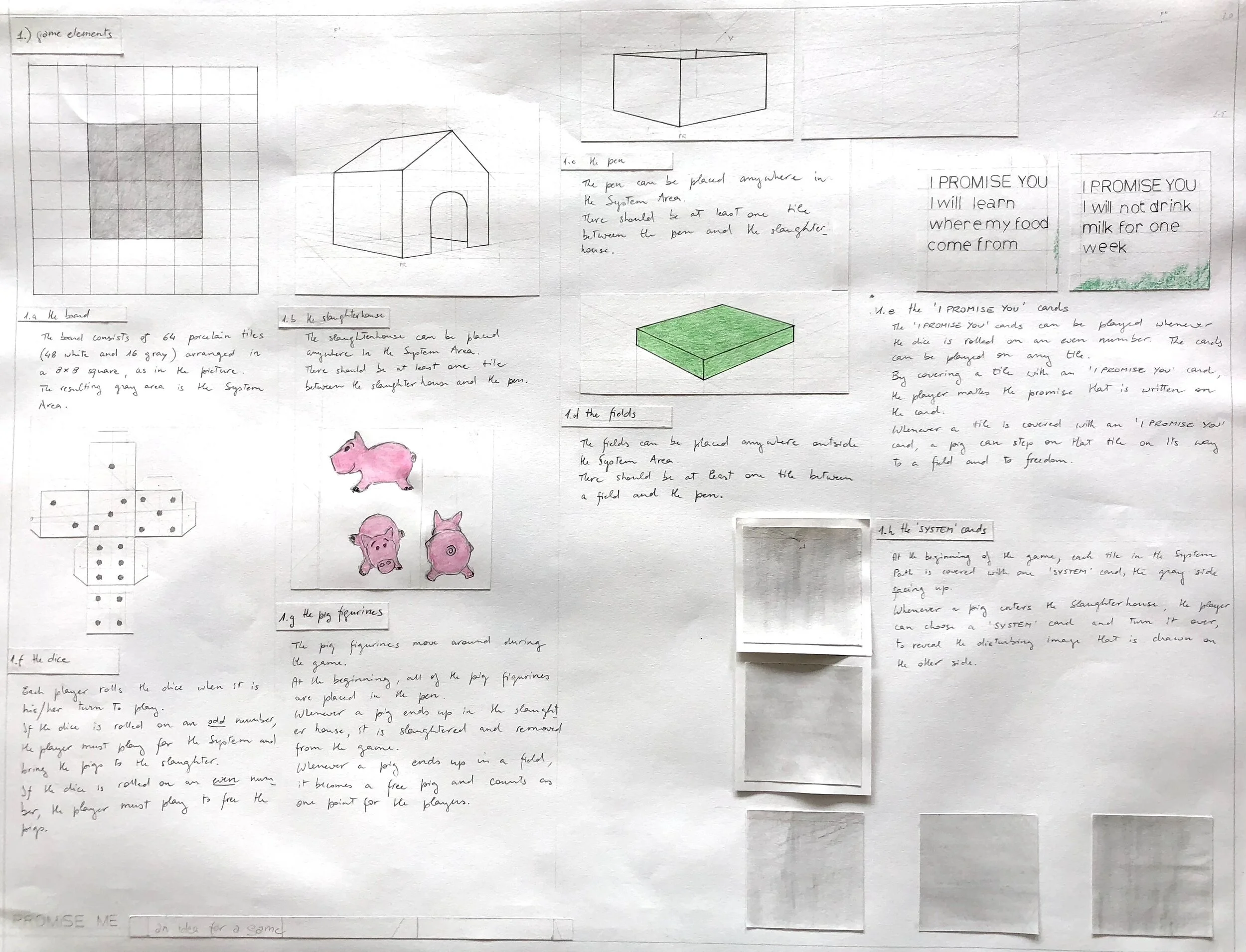

Initial sketches for Promise me, collage on paper, 2018.

On Art and Truth

Here I would like to discuss a text by art critic Boris Groys, published on e-flux in 2016. I do not need to discuss the whole text. I only need the initial part, before Groys reflects on the impact of the internet on art.

Groys opens his text by saying that “The central question to be asked about art is this one: Is art capable of being a medium of truth? This question is central to the existence and survival of art because if art cannot be a medium of truth then art is only a matter of taste.”

There are many ways in which something can be said to be “a medium of truth”, so Groys sets the context of the discussion by choosing a very specific approach: to be a medium of truth in the sense of being a practice that is undertaken within a field of personal responsibility. He opposes the art system to other collectives: “Our world is dominated by big collectives: states, political parties, corporations, scientific communities, and so forth. Inside these collectives the individuals cannot experience the possibilities and limitations of their own actions—these actions become absorbed by the activities of the collective. However, our art system is based on the presupposition that the responsibility for producing this or that individual art object, or undertaking this or that artistic action, belongs to an individual artist alone.”

The notion of truth that Groys advocates is actually more of a notion of authenticity, in the sense of existentialism, where authenticity is the degree to which an individual’s actions are congruent with their beliefs and desires, despite external pressure, but this reading is very interesting for me, because it allows Groys to continue and asks “To what degree and in what way can individuals hope to change the world they are living in?” - a question that will bring the discussion very close to the concepts of persuasive games and moral learning games that I introduced before.

According to Groys art can influence the world in two ways: 1) “Art can capture the imagination and change the consciousness of people. If the consciousness of people changes, then the changed people will also change the world in which they live. Here art is understood as a kind of language that allows artists to send a message. And this message is supposed to enter the souls of the recipients, change their sensibility, their attitudes, their ethics.” Or 2) “Art is understood not as the production of messages, but rather as the production of things. Even if artists and their audience do not share a language, they share the material world in which they live. As a specific kind of technology art does not have a goal to change the soul of its spectators. Rather, it changes the world in which these spectators actually live—and by trying to accommodate themselves to the new conditions of their environment, they change their sensibilities and attitudes. Speaking in Marxist terms: art can be seen as a part of the superstructure or as a part of the material basis.” Art as ideology is contrasted with art as technology, then Groys continues with a discussion of how these two modes of conceiving the artistic practice interact with the contemporary situation of mass production of art due to the presence of the internet. I will not follow this discussion, because it is irrelevant to my research. I will just remain with the contrast between art as ideology vs. art as technology.

Art as ideology requires the artist to speak the same language as her audience. And many modern and contemporary artists have tried to build a common language with their audiences by the means of political or ideological engagement of one sort or another. It seems however that, to be effective, politically engaged art needs to be liked by its audience, thus running the risk of being rejected as ‘really good art’ because of a suspicion of being conventional, banal, merely commercially oriented. Art as technology does not require a community of language and taste with its audience. In fact, the idea is exactly that the contemporary audience will not understand and will not like the art because it is not yet ready for it, and this is why the art aims at being transformative (examples are the radical artistic avant-garde, like Russian constructivism, Bauhaus, or De Stijl.) “The art of the avant-garde did not want to be liked by the public as it was. The avant-garde wanted to create a new public for its art. Indeed, if one is compelled to live in a new visual surrounding, one begins to accommodate one’s own sensibility to it and learn to like it.” The problem here is that the art may be so disliked and misunderstood that it is completely rejected, and thus cannot obtain its effects.

These two notions of art as ideology and art as technology are both present in an artwork which is also a persuasive game. The ideological aspect of a persuasive game is given by its narrative, but also by its procedural rules. What is interesting is that in the case of a persuasive game the transformative message that the artwork wants to transmit does not only rely on a common language, it relies on a psychological structure (the attitude - behaviour construct) and therefore does not necessarily need to seduce: its transformational force does not lay in its seductive character, it lays in its persuasive character.

The technological aspect of a persuasive game is given by its material instantiation, by its being a thing in the world. Of course this materiality can be exploited to transform the world and give insight to a future utopian dimension, but it does not necessarily need to. Since the transformative force of the artwork relies on its ideological character, the technological aspect can be used to make the artwork appealing and turn it into a lure (something that tempts the audience into playing it.)